Centre for

Contemporary

Photography

Current exhibition:

‘Auto-Photo: A Life in Portraits’, June 5 – Aug 16, 2025

RMIT Gallery, 344 Swanston St, Melbourne

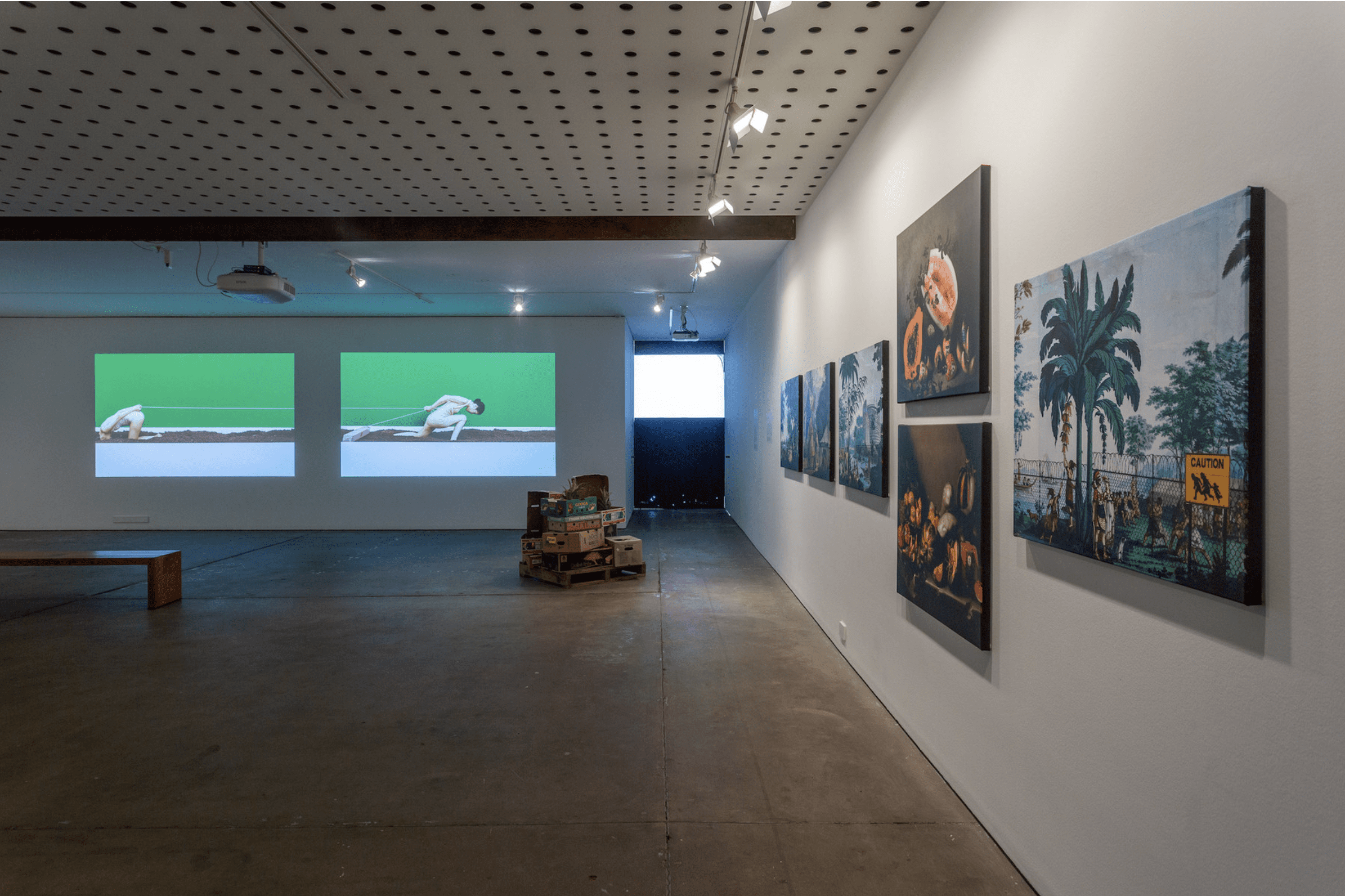

Fertile Ground brings together nine artists who use food as an entry point to discuss urgent political, societal and environmental issues. The artists offer food as a tool for activism, cultural exchange, repositories of history and visions for the future.

Physical, cultural and ideological ramifications of food production, circulation and consumption are examined by artists Elia Nurvista (Indonesia) and Lauren Dunn (Australia). Nurvista focuses on the impact of colonial power and exploitation on food farming, production and marketing. Produce and customs are commodified and sold as exotic, luxury items or experiences with total disregard for their native countries, communities and farming conditions. Dunn too highlights this in her series New Romanticism where she draws attention to societal romanticised relationships with food and food culture. In the installation Luxury item no.13 she physically places the oyster as a prized possession elevated upon a quasi-throne to emphasise idealised food hierarchies and structures.

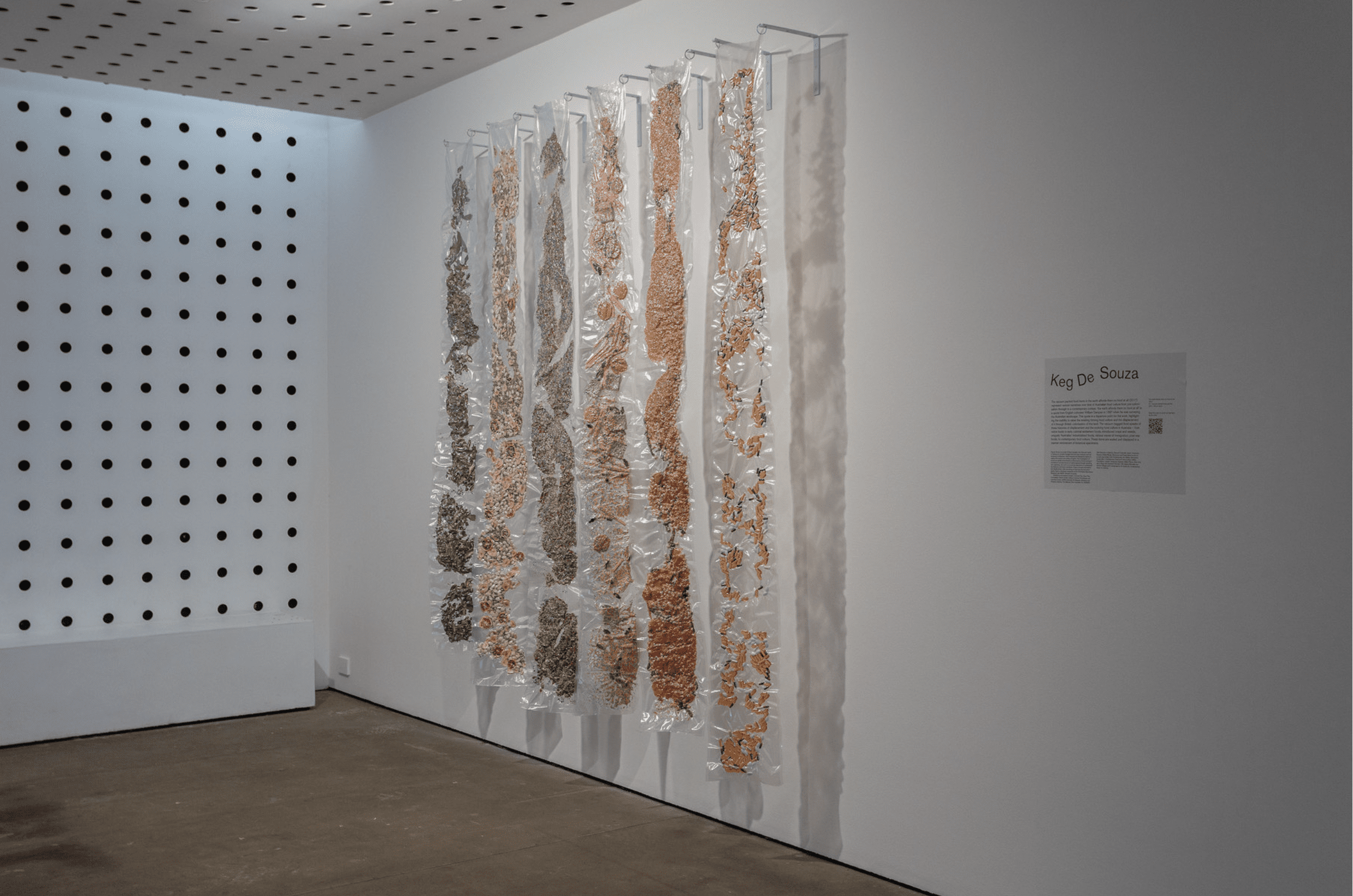

The works by James Tylor (Australia) and Keg de Souza (Australia) continue interrogating colonial impact on Indigenous food sources and scarcity, highlighting the historical and contemporary inability to recognise and value indigenous farming and traditional practices in caring for native ecosystems. Tylor presents recipe cards informed by indigenous and non-indigenous ingredients, inviting visitors to take away the recipe and consider investigating, cultivating and cooking with native and introduced ingredients to decolonise their pre-existing relationship with food. De Souza’s practice focuses on scrutinising community food, space and displacement. In the work The earth affords them no food at all… specimens of indigenous ingredients, imported crops and food samples from the many waves of migration work as a record of displaced, diasporic and frontier food narratives within Australian history and culture.

Fertile ground accepts any and everything that is planted but, with disruption and lack of nourishment, the reality of failure and loss is inevitable. Kim Hak (Cambodia), Shivanjani Lal (Australia) and Sophal Neak (Cambodia) investigate the fragility of existence and create repositories for memories. They explore landscapes as shifting sites, lament the loss of ancestral land and question the temporality of place. As an ancestral survivor of the Khmer Rouge regime, Kim reflects upon the cycles of life and relationship to his father and the land in his Sunset series, and Lal on her familial history and relationship between lands (India and Fiji) in her Chaapaa series. Shivanjani shares a series of images that are enlarged polaroids, reminiscent of a family travel album, reprinted in India onto brown paper and documenting a contemporary and changing Fiji. As Lal highlights forgotten pasts, artist Neak also gives voice to those who cannot speak for themselves in her project Rice Pot. Neak, a performative photographer driven by storytelling, explores societal pressures, traditions and responsibilities of women to nourish the community. Her photographs are the result of ongoing conversations with women from her ancestral village who found a collective voice in Neak’s visits and community workshops.

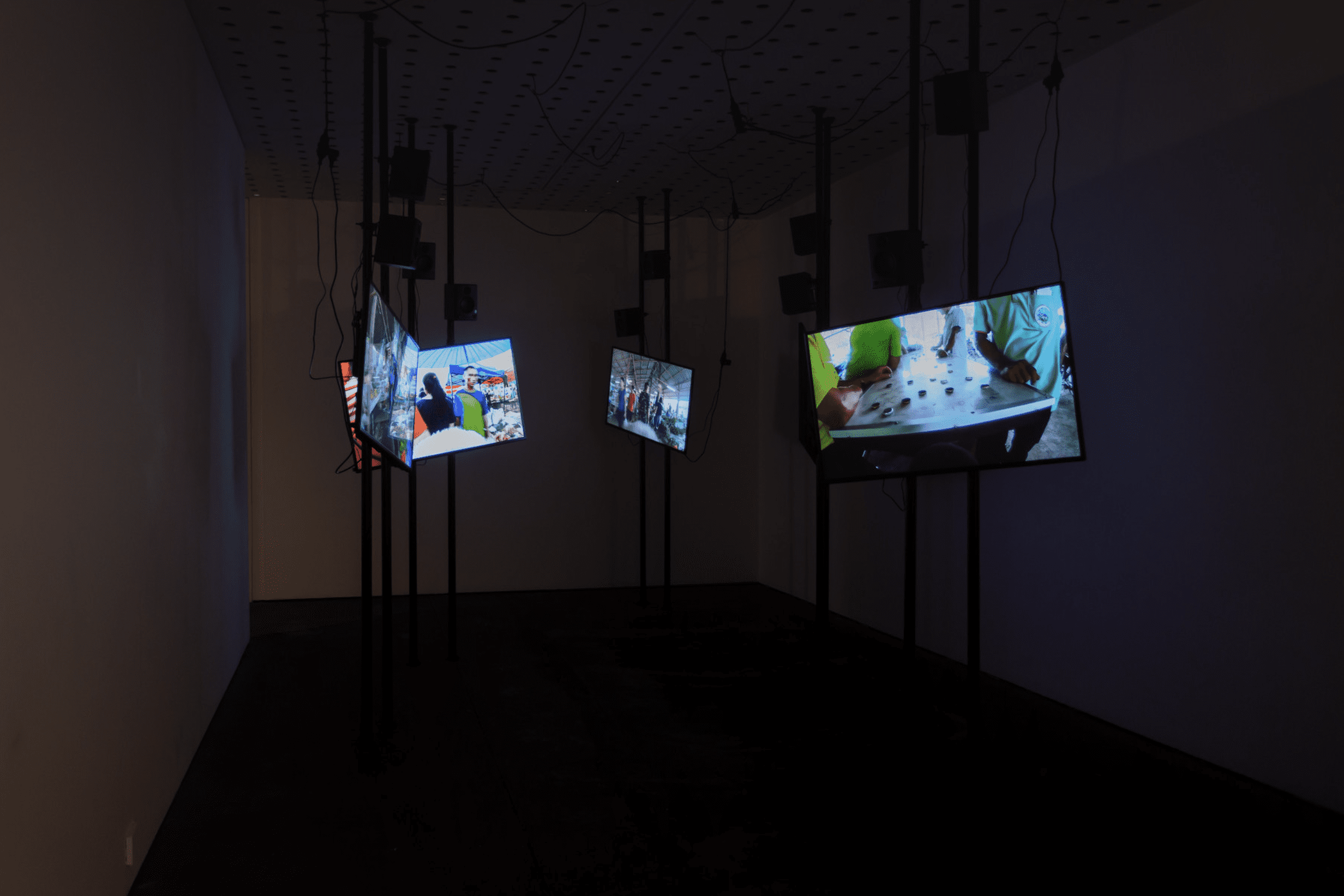

Kawita Vatanajyankur (Thailand) and Arnont Nongyao (Thailand) explore the systems of trade and farming practice. In her Field Work series, Vatanajyankur appears silent in her physical transformation from woman to essential farm machinery who prepares the ground for harvest. Her rhythmic and robotic pattern appears endless and pointless. As Vatanajyankur engages in the act of production, Nongyao celebrates the results in screen and sound work, Opera of the Kard. An immersive operatic soundscape shares the ‘vibration’ of community at a local kard (market) with layered voices of the farmers selling their produce.

Interrogated through the mediums of photography, video, sculpture and installation, the participating artists enable new perspectives and explorations in social space and thinking. Shared reflections on the uncertainty of place, the fragility and temporality of land, may raise anxieties about where we now find ourselves, while also empowering a collective consideration for a bountiful future, a fertile ground, on which to regenerate and rethink.

Join Dr. Wulan Dirgantoro, McKenzie Postdoctoral Fellow, School of Culture and Communication, University of Melbourne in conversation with participating artists Elia Nurvista and Shivanjani Lal, as they discuss their works exhibited in Fertile Ground and broader artistic practice. The artists will explore a shared connection around the effects and exploitation on food production and the impact of colonial power on land.

Join curator Natalie King OAM, Professor of Visual Arts at the VCA, University of Melbourne, in conversation with exhibiting artists Kim Hak, Kawita Vatanajyankur and Arnont Nongyao as they discuss their photographic and broader artistic practice. Artists will explore how we measure and treasure the ‘vibrations’ of a community through food exchange, the physicality of food trade and the unseen effects of commodification and industry. Themes touch on climate change, immersion and seduction of the exotic and death as all things return to the soil – nature’s keeper of secrets.

Join artist-researcher, facilitator and educator Dr. Jen Rae in conversation with participating artists Lauren Dunn, Keg de Souza, Sophal Neak and James Tylor as they discuss their works exhibited in Fertile Ground and broader practice. The discussion will be themed around issues such as food scarcity, systems knowledge, hierarchies, and the role of women and community.

Public programs for Fertile Ground were presented with the support of the University of Melbourne’s Centre of Visual Art.

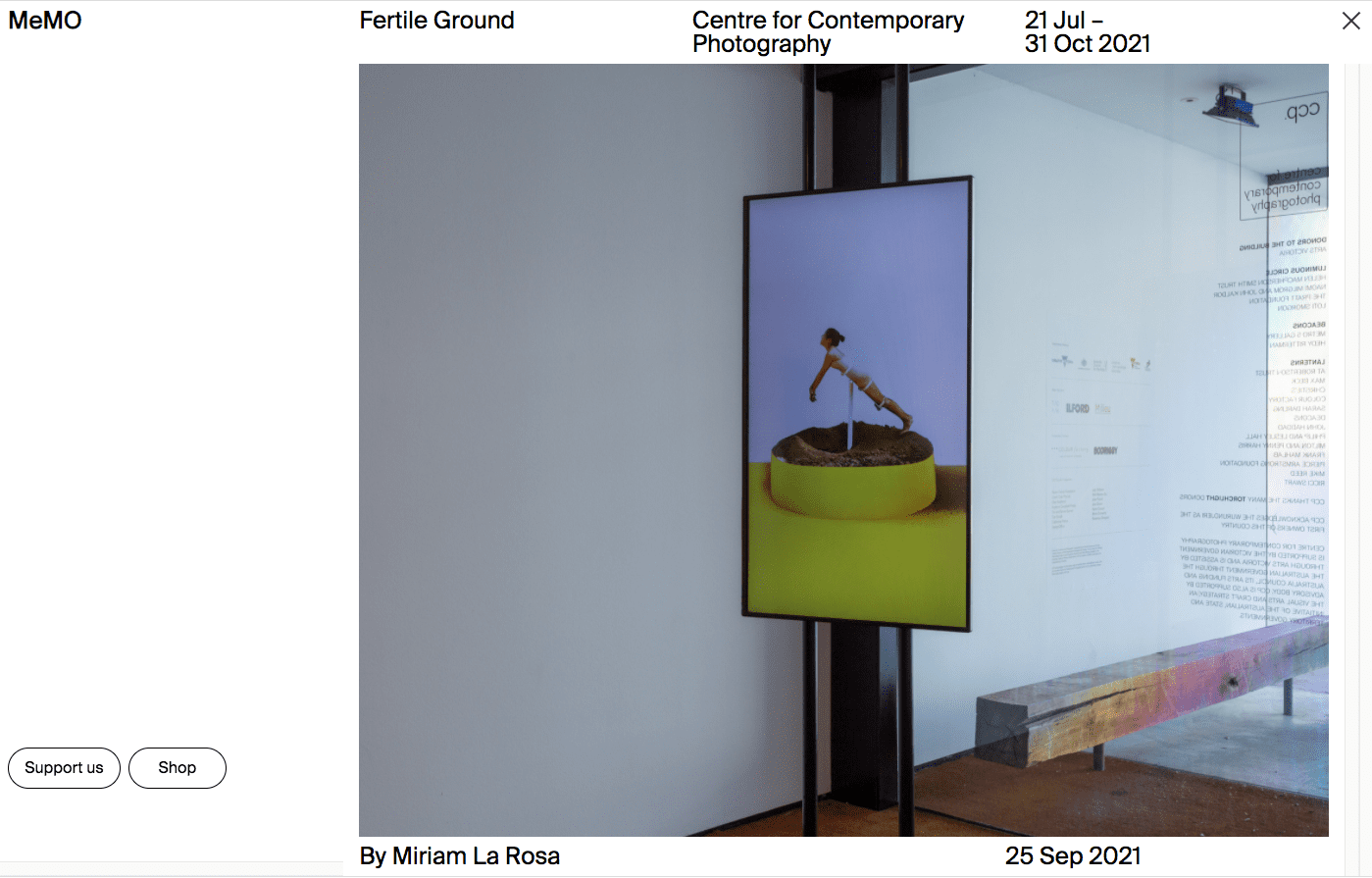

Read Miriam La Rosa’s review of Fertile Ground in Memo Review, Melbourne’s only weekly art criticism, published each Saturday morning.

Notifications