Centre for

Contemporary

Photography

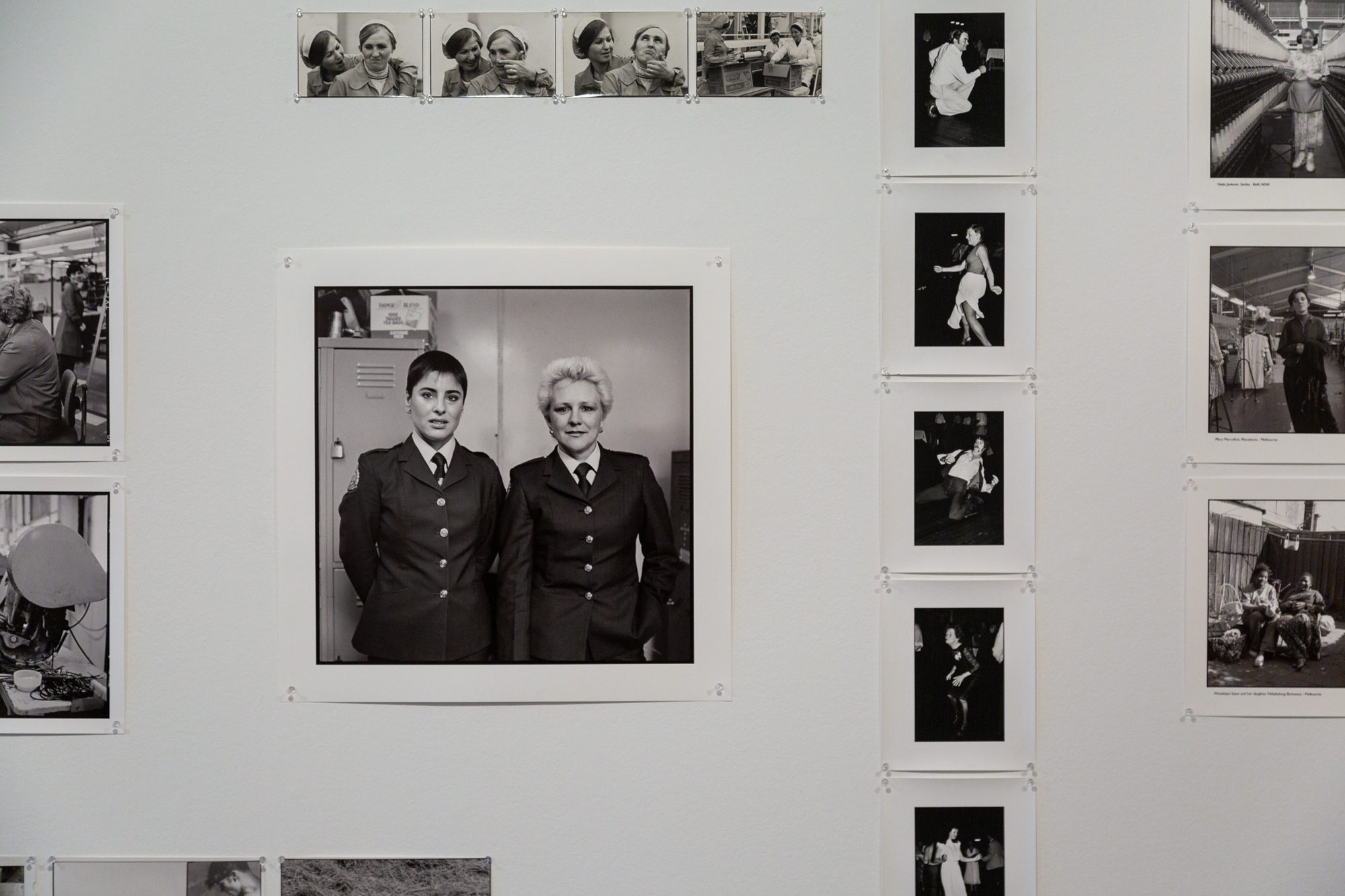

Current Exhibitions:

FAMILIAL, Town Hall Gallery, Hawthorn

AUTO-PHOTO: A LIFE IN PORTRAITS, Frankston Arts Centre

Gallery Hours:

FAMILIAL: Mon to Frid 9-5, Sat 12-4

AUTO-PHOTO: Tues to Frid 10-5, Sat 10-2